Care – By @philgull

By Philip Gull

Care

English is a simple language. It only has four kinds of words.

There are big words and long words, little words and short words.

The first mistake you make is thinking that big words and long words are natural partners.

This gets you called a pretentious c*nt.

The second mistake you make is thinking that big words have to be short exclusively.

Unless your name is Mr. Hemingway but all your friends call you Ernest, this may also backfire, and you may become the proprietor of boring prose, and terser verse.

Big words come in all shapes and sizes.

A Big Word is a word that you can’t ignore. It inverts the normal person-word relationship. Most words are at our service. We use them, we do work with them. But Big Words get to work on us. You can try to contain a Big Word through context and syntax, but it doesn’t ever lie still. Big Words are not only what we use to express our big thoughts; when we read them, or see them, they shed light on other people’s Big Thoughts and become catalysts for more of our own.

Big-Short Words are particularly pleasing: an economy of writing for an expanse of thought.

One of my favourite Big-Short words is ‘care’. It’s a Big Old Word. It’s in Beowulf.

(If you want to read something good about ‘care’, please skip this SCAB and go straight to its OED entry, which is 1,927 words long. It’s a Big Word.)

What should I do in life? is really what do I ‘care’ about? rephrased.

How does care relate to creativity? is one of the questions I ask myself most often.

Should I care what I make? Or should I just make it? Should I care what anyone else thinks of it?

Am I caring enough about Marc’s advice? Am I caring too much?

Once at SCA, should I care? Should I care and conform? Should I toe the line? How long should you care for? Is rebelling caring too much, or too little?

Should I care what everyone else thinks of me? Is indifference still different anymore?

Care is really difficult.

One thing I know for certain I care deeply about: my heroes.

When I was picking what uni I wanted to go to, I didn’t really care about course prospectuses or syllabuses or league tables or cool years abroad or what the student accommodation was like or library renovations or new sports facilities or staying close to my family or getting as far away from them as possible or where all my friends were going or what uni my grandma wanted me to go or how to keep my teachers happy.

I cared about my heroes. I was going to be studying them for three years, after all. So I went after them.

I went to the same college as one of my biggest heroes, Edmund Spenser.

Edmund Spenser was a poet and a genius.

He was genius who made the rather large mistake of being born at the same time as one limelight-stealing bardstard, William Shakespeare. But what a glorious underdog he became.

Edmund Spenser cared deeply about care and how it related to creativity.

In his allegorical poem The Faerie Queene, he turns care into Care, an agonised, dishevelled blacksmith:

Rude was his garment, and to rags all rent,

Ne better had he, ne for better cared:

With blistred hands emongst the cinders brent,

And fingers filthie, with long nayles vnpared,

Right fit to rend the food, on which he fared.

His name was Care; a blacksmith by his trade,

That neither day nor night from working spared,

But to small purpose yron wedges made;

Those be vnquiet thoughts, that carefull minds inuade. (IV.v.35)

Spenser’s ‘Care’ is a walking, personified pun, combining both the verb (to feel concern, or interest) and noun (sorrow, grief) forms of ‘care’. His ‘care’ for his artistry as a blacksmith overrides his natural ‘care’ for his own well-being, inhibiting his creativity so that only ‘yron wedges’ to ‘small purpose’ are made. He emblematises the paradox of care and creativity: care too much about your craft, to the extent that you transform into Care, and you can lose your artistry and originality. A ‘carefull mind’ isn’t always conducive to creativity.

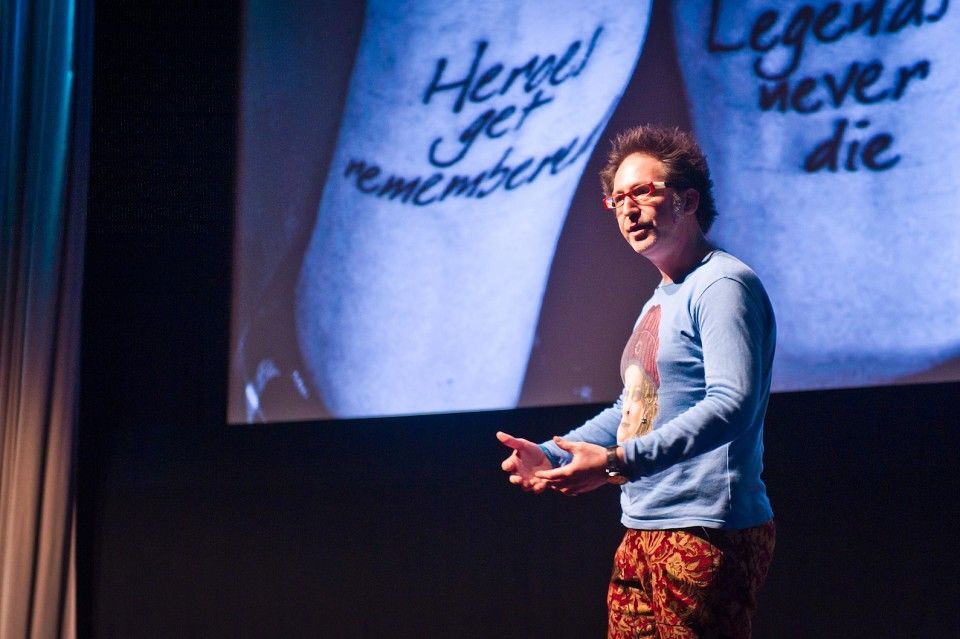

Marc’s got the hero angle covered pretty well at SCA. When I scoped out SCA in April before my interview, Marc was on holiday. Steve Harrison was running the school.

Watford became Notford pretty quickly after that. Sorry, Tony.

Edmund Spenser, as you’ve probably guessed, was either a terrible speller or isn’t with us anymore. He died in 1599.

A particular benefit of SCA is that it specialises in nice, healthy mentors. I’m looking forward to that.